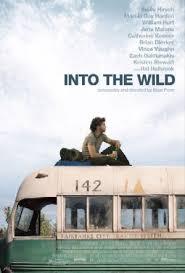

Into the Wild

One of Chris’s managers at McDonald’s said that he worked at a “slow pace” and came to work “smelling bad” (40-41). The smell part reminded me of the elder Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov. This kind of image of a man is rather unsavory and base. And yet, we have the letter Chris wrote to the 80-year-old Franz, which is poetic and inspiring. How can these two poles exist in the same person? As I thought about this, I understood a little better the importance and the significance of Alyosha kissing the earth and accepting everything. What he was accepting was Chris McCandless, and the Chris McCandless in all of us… that part or parts or whatever it is that can be base and mean and ugly but at the same time be capable of such beauty and inspiration and giving. Alyosha was accepting all the bad because he knew that that was part of the package, part of being human, and that even the basest person is capable of kindness.

I like the setup of the book. The scenes switch back and forth from Chris traveling the West and living in Alaska to the remembrances of the people who knew him as he was traveling. Then there is the chapter that deals with Krakauer’s own story and how it is similar in many ways to the Chris McCandless story. I thought this was a great interlude in the book, since it is really the very reason why the book was written, why Krakauer was so fascinated with the Chris McCandless story.

Each chapter begins with these great quotes from guys like Paul Shepard, London, Thoreau and Tolstoy. Just some really good, good, stuff. And, in fact, a lot of these quotes at the beginning of these chapters deal with nature and the reasons people go into it. There is this thread throughout the book that deals with the difficulty of figuring out why anyone would want to walk into the woods, or climb a mountain, or just be alone. There is also the added mystery of figuring out why someone would want to do something dangerous, like climb an ice cliff. On one level, therefore, the book is just a great adventure read and a real page turner. But Krakauer does a lot more here… He uses these heavy hitters to open up his chapters to illustrate the incredible complexity of the questions that McCandless’s trip brings to the fore. He uses them to offer possible reasons for McCandless’s actions, and his own. Shepard, for example, writes that men have gone into the desert “not to escape but to find reality” (25). This reminds me of an answer that Frost gave to someone who asked him if he was trying to escape reality through his poetry and he responded by saying something to the effect of “No, I meet it head on.” To me, I understand exactly where Frost was coming from, but I sometimes wonder if it is a razor’s edge that we poets are straddling. Chapter six opens up with a quote from Thoreau where he exclaims that “The greatest gains and values are farthest from being appreciated… They are the highest reality.” There is definitely something being sought in solitude and nature that does not seem to be available among the crowds and in the cities.

I have often wondered how our detachment from nature affects us or changes us or diminishes our life experience. We live in houses, cars, buildings, malls, and our feet hardly every touch soil and our hands rarely touch a tree. In that sense, we can begin to see why we sometimes have the urge to live in nature completely. But then there is the solitary aspect of it all that complicates it. Krakauer, like McCandless, desired to go into the woods alone. So, yes, there is the “intimacy with nature” element, but there is also the “solitary” element as well, the desire to not stay in one place or with one person too long. When Chris left Franz, Krakauer writes of Chris that “he was relieved as well — relieved that he had again evaded the impending threat of human intimacy, of friendship, and all the messy emotional baggage that comes with it” (55). In his incredible letter to Ron Franz, Chris himself writes that “The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun” (57). It very much reminded me of Emerson’s observation that he was “an endless seeker with no Past at my back”, or Chang-rae Lee’s character Jerry in Aloft. It may be helpful to look at Jerry’s “recurring fantasy” of “perfect continuous travel, this unending hop from one point to another, the pleasures found not in the singular marvels of any destination but in the constancy of serial arrivals and departures, and the comforting knowledge that you’ll never quite get intimate enough for any trouble to start brewing” (212). This idea of never getting too intimate is echoed by the character Doc Hata in Chang-rae Lee’s novel A Gesture Life where, interestingly enough, Doc Hata is describing the spring junkets he took with his business associates to Myrtle Beach: “what I looked forward to each year with genuine fondness was being with fellow businessmen, and passing those easy, jocular hours of camaraderie by the pool or greenside or in a smoky bar, when we spoke of nothing profound or consequential” (19). Chris’s letter to Franz echoes these sentiments.

I am also wondering what to make of the connection between reality and life. To be more specific, is a heightened sense or awareness of reality equivalent to a more intense experience of living? I’m not sure if the distinction is important and maybe I am just playing a word game here, but I thought of the different levels of emotional intensity that the book comments on. Krakauer, who is engaged in a risky climbing venture alone, comments that “The unnamed peaks towering over the glacier were bigger and comelier and infinitely more menacing than they would have been were I in the company of another person. And my emotions were similarly amplified: The highs were higher; the periods of despair were deeper and darker” (138). Of Thoreau’s experience on Katahdin, he writes that “His ascent of the peak’s ‘savage and awful, though beautiful’ ramparts shocked and frightened him, but it also induced a giddy sort of awe” (183). Reading these excerpts, I thought of Kant and his notion of the sublime, which involves concepts such as infinity or terror. Could it be that another reality — a higher reality? — (God?) can only be accessed by engaging in activities where we come into contact with the “infinite” or terrible?

One of the places in the book where Krakauer comes closest to figuring Chris(and himself) out is when he states “When I decided to go to Alaska that April, like Chris McCandless, I was a raw youth who mistook passion for insight and acted according to an obscure, gap-ridden logic. I thought climbing the Devil’s Thumb would fix all that was wrong with my life. In the end, of course, it changed almost nothing.” I don’t fully trust Krakauer here. He states “almost nothing” but then he fails to tell us what it did change and whether that made it worth it or not. Certainly, Krakauer went on to do similarly risky activities, so we have to assume that he was getting something out of it. He leaves us hanging, however, and later in the book, he admits that Chris’s “essence remains slippery, vague, elusive” (186).

I like the setup of the book. The scenes switch back and forth from Chris traveling the West and living in Alaska to the remembrances of the people who knew him as he was traveling. Then there is the chapter that deals with Krakauer’s own story and how it is similar in many ways to the Chris McCandless story. I thought this was a great interlude in the book, since it is really the very reason why the book was written, why Krakauer was so fascinated with the Chris McCandless story.

Each chapter begins with these great quotes from guys like Paul Shepard, London, Thoreau and Tolstoy. Just some really good, good, stuff. And, in fact, a lot of these quotes at the beginning of these chapters deal with nature and the reasons people go into it. There is this thread throughout the book that deals with the difficulty of figuring out why anyone would want to walk into the woods, or climb a mountain, or just be alone. There is also the added mystery of figuring out why someone would want to do something dangerous, like climb an ice cliff. On one level, therefore, the book is just a great adventure read and a real page turner. But Krakauer does a lot more here… He uses these heavy hitters to open up his chapters to illustrate the incredible complexity of the questions that McCandless’s trip brings to the fore. He uses them to offer possible reasons for McCandless’s actions, and his own. Shepard, for example, writes that men have gone into the desert “not to escape but to find reality” (25). This reminds me of an answer that Frost gave to someone who asked him if he was trying to escape reality through his poetry and he responded by saying something to the effect of “No, I meet it head on.” To me, I understand exactly where Frost was coming from, but I sometimes wonder if it is a razor’s edge that we poets are straddling. Chapter six opens up with a quote from Thoreau where he exclaims that “The greatest gains and values are farthest from being appreciated… They are the highest reality.” There is definitely something being sought in solitude and nature that does not seem to be available among the crowds and in the cities.

I have often wondered how our detachment from nature affects us or changes us or diminishes our life experience. We live in houses, cars, buildings, malls, and our feet hardly every touch soil and our hands rarely touch a tree. In that sense, we can begin to see why we sometimes have the urge to live in nature completely. But then there is the solitary aspect of it all that complicates it. Krakauer, like McCandless, desired to go into the woods alone. So, yes, there is the “intimacy with nature” element, but there is also the “solitary” element as well, the desire to not stay in one place or with one person too long. When Chris left Franz, Krakauer writes of Chris that “he was relieved as well — relieved that he had again evaded the impending threat of human intimacy, of friendship, and all the messy emotional baggage that comes with it” (55). In his incredible letter to Ron Franz, Chris himself writes that “The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun” (57). It very much reminded me of Emerson’s observation that he was “an endless seeker with no Past at my back”, or Chang-rae Lee’s character Jerry in Aloft. It may be helpful to look at Jerry’s “recurring fantasy” of “perfect continuous travel, this unending hop from one point to another, the pleasures found not in the singular marvels of any destination but in the constancy of serial arrivals and departures, and the comforting knowledge that you’ll never quite get intimate enough for any trouble to start brewing” (212). This idea of never getting too intimate is echoed by the character Doc Hata in Chang-rae Lee’s novel A Gesture Life where, interestingly enough, Doc Hata is describing the spring junkets he took with his business associates to Myrtle Beach: “what I looked forward to each year with genuine fondness was being with fellow businessmen, and passing those easy, jocular hours of camaraderie by the pool or greenside or in a smoky bar, when we spoke of nothing profound or consequential” (19). Chris’s letter to Franz echoes these sentiments.

I am also wondering what to make of the connection between reality and life. To be more specific, is a heightened sense or awareness of reality equivalent to a more intense experience of living? I’m not sure if the distinction is important and maybe I am just playing a word game here, but I thought of the different levels of emotional intensity that the book comments on. Krakauer, who is engaged in a risky climbing venture alone, comments that “The unnamed peaks towering over the glacier were bigger and comelier and infinitely more menacing than they would have been were I in the company of another person. And my emotions were similarly amplified: The highs were higher; the periods of despair were deeper and darker” (138). Of Thoreau’s experience on Katahdin, he writes that “His ascent of the peak’s ‘savage and awful, though beautiful’ ramparts shocked and frightened him, but it also induced a giddy sort of awe” (183). Reading these excerpts, I thought of Kant and his notion of the sublime, which involves concepts such as infinity or terror. Could it be that another reality — a higher reality? — (God?) can only be accessed by engaging in activities where we come into contact with the “infinite” or terrible?

One of the places in the book where Krakauer comes closest to figuring Chris(and himself) out is when he states “When I decided to go to Alaska that April, like Chris McCandless, I was a raw youth who mistook passion for insight and acted according to an obscure, gap-ridden logic. I thought climbing the Devil’s Thumb would fix all that was wrong with my life. In the end, of course, it changed almost nothing.” I don’t fully trust Krakauer here. He states “almost nothing” but then he fails to tell us what it did change and whether that made it worth it or not. Certainly, Krakauer went on to do similarly risky activities, so we have to assume that he was getting something out of it. He leaves us hanging, however, and later in the book, he admits that Chris’s “essence remains slippery, vague, elusive” (186).